An ode to footnotes, references, and compilations.

A few years ago I picked up Michael Chabon’s Bookends, a short essay collection championing introductions, forwards, prefaces, epilogues, and postscripts – you know: the stuff before and after the book you showed up to read. While every decent book could – hell, should- very well stand on its own without introductions or postscripts, I tend to get a lot more out of the story when I can pick up additional context and further readings.

The story – from once upon a time to happily ever after – is enough to sustain most people, but the added barnacles of information, links, and sources is where I’ll spend far too much time. Lately, with my slow-read through of Infinite Jest, I am finding a lot of my time with the book is spent parsing through the footnotes (which the editor of this edition has collectively placed at the back of the book, instead of the bottom of the page)1 and getting carried off into all sorts of other directions for upwards of a half hour at a stretch before I collect myself and find the spot in the main story where I last left off.

“Existence is a series of footnotes to a vast, obscure, unfinished masterpiece,” waxed Vladimir Nabokov. On the other end of the spectrum is playwright Noel Coward: “Having to read footnotes resembles having to go downstairs to answer the door while in the midst of making love.”

I guess it all depends on who is at the door.

The internet has forgotten about the bottom of the page. The top of the page is king. After all, it’s the first thing your audience sees, it is where the search engines crawl about and look for relevant information to bring audiences to you. Focus on the headers, the titles! The further to the bottom you go, the less people care about typos and errors. Some pages have no bottom, they just endlessly scroll loading one bit of code after the next, pulling one article after another out of an invisible archive. If there is a bottom, that’s where all the legalese and fine print lives, or the pagination arrows that are rarely clicked – will the next page really give us anything different?

Unless you’re on something as simple as a Wikipedia page – where the bottom of an article is the repository of “Notes and References, Sources, Further Reading, and External Links.” 2 These are the links that take you outside of the website and into the strange parts of the internet, beyond the algorithmically filled front pages of major news sites and off into indie publications and passion projects. I’d wager half of the links are dead or will drag you to a cruelly-slow archive page, or you might wind up on the most fascinating fan-derived database you’ve ever seen.

The trick is finding these databases, the fan sites, these domains set up for the capture of very specific ideas. These blogs, if you will. Otherwise, we’re stuck with the algorithmic scum that festers on the surface of every pool of cool stuff (the cool stuff, again, being at the bottom).

Consider Spotify – the exploitative audio hellscape that has completely overturned the music industry, again, in a way like we haven’t seen since the Napster and Limewire days. This time, somehow, it is more legalish as the record publishers are in cahoots with the platform to ensure certain tracks get all the attention (and therein, the revenue). The promise of “discovery” on Spotify is but a joke. The daily mixes they cobble together haven’t been refreshed in ages. Yet, you can still find good stuff…if you go to the bottom of the pages.

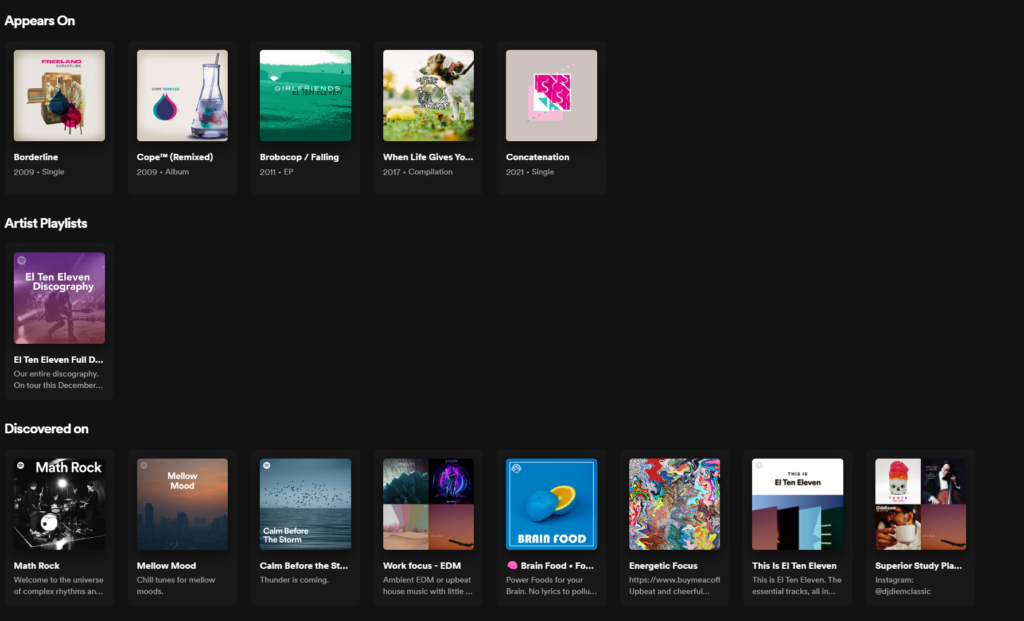

On a whim, here is what’s below the fold for El Ten Eleven‘s3 verified artist page:

If you’re looking for similar, but not the same, it’s a good collection of math rock/ ambient/ modern instrumentals. “Appears on” is where the artist has officially published on other compilations or artist albums. “Discovered on” is anywhere their music is found on a public playlist. Obviously, Spotify takes top spots for themselves, but the user-curated playlists have some great gems.

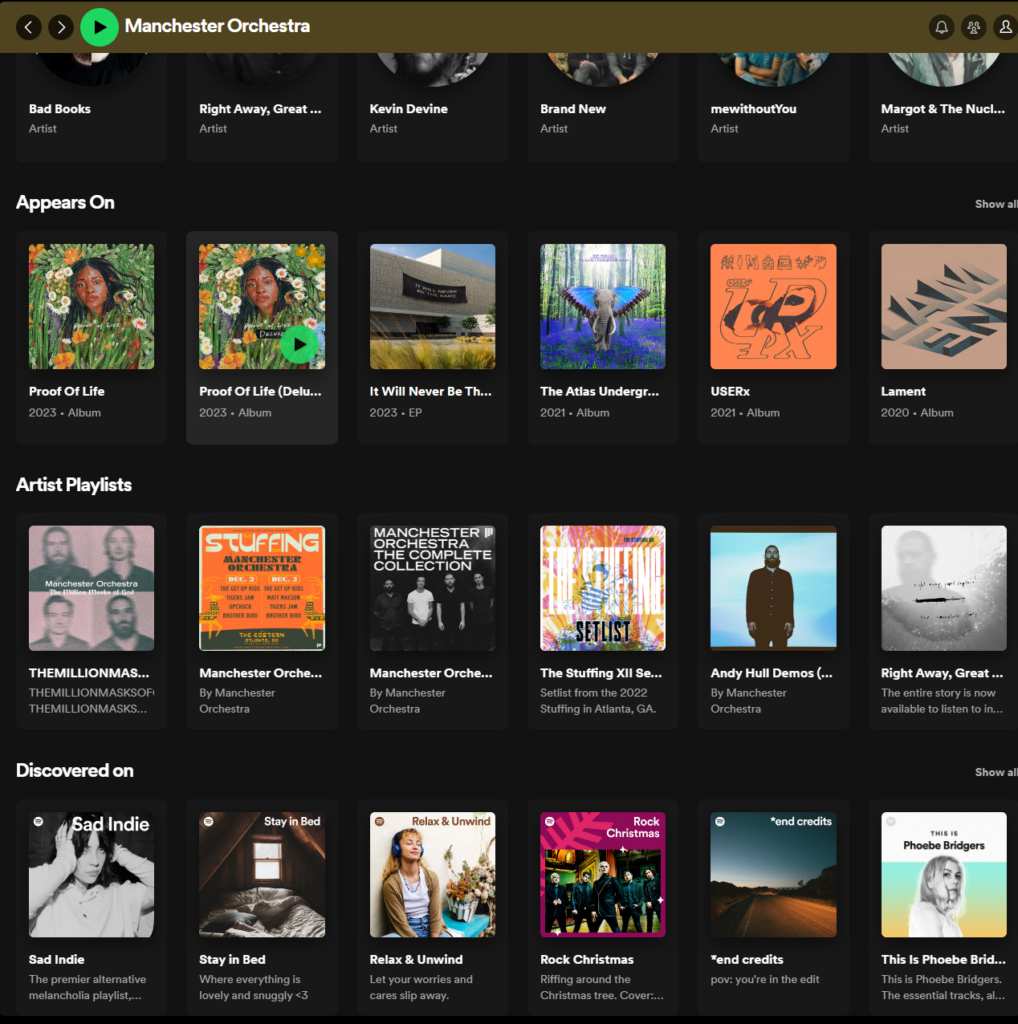

Looking over at Manchester Orchestra‘s page:

Appears on, Discovered On, and the delightful mix of the Artist Playlists. This is like reading what your favorite author is reading. In my experience, these playlists are a vast departure from the kind of music the artist writes for their own projects.

Although, looking at the above screenshot – not sure I would lump these guys in with the “Sad Indie” crowd. Alas.

So yeah, keep scrolling to the bottom. The right places will have the best stuff.4

- Then again, David Foster Wallace is known for crafting entire short stories within the margins and footnotes. Some notes are to break out an abbreviation, others go on for pages in fantastic detail at 8 pt font. ↩︎

- All separate sections, all of varying quality and density depending on the topic and the public interest. I tried my hand at contributing to Wikipedia a few years ago, and then again a few weeks ago – in those years, the community grew up and grew cold. There is no chance of starting off a new stump, no chance of playing around, and everything you add or contribute is placed under the most cynical microscope – something I would typically be all about, but only when it’s not MY work under scrutiny. ↩︎

- Linking to Bandcamp pages or artist websites for these artists because if you like them and want to support them, you really ought to just buy the damn albums already. Which I know defeats the purpose of talking about Spotify here. But, seriously, You Should Own Everything On Your Spotify Wrapped. ↩︎

- Like this. ↩︎