All he wanted to do was talk to his son.

The gist of Infinite Jest, or of the four or five books within this book, is that James Incandenza would like to have a conversation with his son, Hal. In doing so, he accidentally creates a movie so endlessly watchable that viewers get stuck in a catatonic state where they are quite literally entertained to death. The plot of the book follows the handful of days where rouge agents from Canada and the ONAN (what the US eventually becomes in the novel) try to track down the master copy of the movie to either distribute (Canada) or prevent the distribution of (ONAN) to the general public in an act of terrorism that would destabilize the welfare of the two countries.

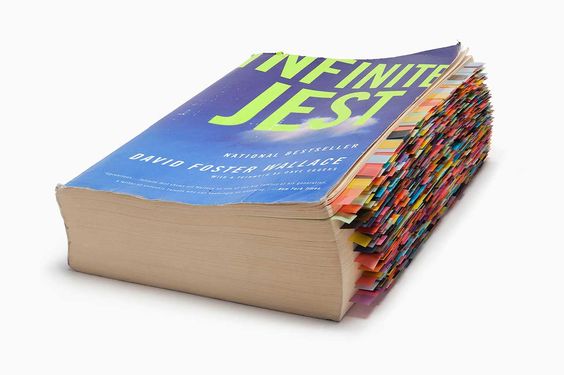

Plus, another 1000 pages of stories, narration, and ever evolving details that are ever fragmenting into smaller slices of information, footnotes, and errata that no human could ever realistically hold in their head at the same time. But, as any decent novel, every rereading reveals something new. The book stays the same, but the reader is different and the world beyond the pages evolves.

At the core, James wanted to talk with Hal. In early childhood, Hal accidentally ingests some kind of filthy mold he finds in the basement (you know how kids are!). He survives, but his mental capacity is never quite the same. In modern parlance, he presents on the spectrum – relatively quiet and overly analytical in his speech with an internal conversation that races. He’s memorized the dictionary. He corrects everyone. He also dials in his interests with a scary level of obsession (marijana and tennis, mostly). But an additional childhood trauma Hal witnesses leaves him unable to converse with his father – who will ace himself (“remove his own map”) years later.

The attempts at these conversations are through Jame’s obsession with film. The idea is that he could create an art film that speaks to something carnal within Hal – something to draw out his emotion and his expression. The final result is a film titled “Infinite Jest” that features an absolute hottie looking down at you, the viewer, as though you were a baby in a bassinet.

Forgive my early analysis – I’m still processing.

I sat down with this tome after the turn of the year because I needed to focus on something. 2023 was the kind of year of self-reflection that revealed a mess of holes in how I viewed the world and the way my mind worked with it. The indefinite campaign to reclaim my brain, my focus, my attention, and turn it back into something I can work with. The act of breaking down and dissecting a 1000-page book is one of self-love. The first readthrough took four months (close reading, lots of notes, intentionally slow), a purposeful act. The goal was to spend an entire year with Infinite Jest – meaning there will be further read-throughs and annotation – rather than it being “the book I am currently reading.” This is the book I read while “sitting up” versus the other novels and nonfiction books I read while lying in bed or while I nod off for a nap.

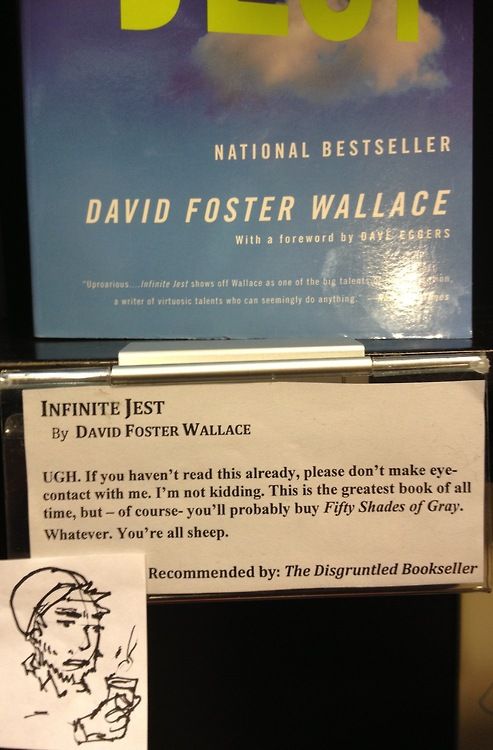

Beyond the heft of the book and its enduring cultural relevance (even though it feels like no one has read the damn thing), the title will always stick out as an invitation. This is my fourth reading of the novel since I picked it up in college because I thought it might get me laid (it did not) and every reading is juxtaposed against the increasing mess of screens I spend my day looking at. In the novel, the media is a thing that gets obsessed over. One character recounts his father dying over his involvement with the TV series M*A*S*H*. The obsession started out cutely enough – the mother ensures dad has a TV dinner ready to eat when he gets home for work in time for the broadcast of the show. Then he would move on to watching every rerun and syndication of the show – keeping careful track of the TV guide and even hiding a TV at work so he could sneak in viewings. Once Betamax came along, it was over. His father closed himself off in a room, Howard Hughes style, and would watch reruns and video replays of the show until his eventual heart attack. It was beyond comforting entertainment – like how so much of my generation can sit through an episode of The Office no matter how many times they’ve seen it – as the father would write out theories of the characters and even send them mail, as though they were real-life veterans, through the broadcast office.

It’s striking to read this in 2024. The theory of endless entertainment from the early 90s when we were all forced into an alley of network or cable channels. Now, much like the technology outlined in the book, we can all order up any conceivable form of video straight to any number of devices. From games to TikToks, we can stay tuned in until our eyes go numb and the dopamine drip dries out – it could be the death of us, if we let it.

The history of Infinite Jest tells of a “600 page slashing” from the original manuscript – no telling what was among those pages. I’d imagine there was a subplot of censorship and propaganda distributed through the video systems – something that is surprisingly absent from the text. So much of the media that is produced in this world starts on “Master tapes” that are either copied and mailed (the postal service is still very much a thing, of course!) or broadcasted to user headsets – meaning there likely isn’t much opportunity for manipulating the contents. Meanwhile, here in our grim present day world of loose and fast understanding of DRM, digital media is routinely cut, edited, chopped, censored for cable broadcast, and more – fitting with the mediums, fitting with the culture, no matter where in the world it may be.

I’m giving myself two weeks to digest the notes from this reading (also, I’m traveling internationally and Infinite Jest is not exactly “portable”) before I start the next reading. Since so much of it is fresh, the reading will likely be faster but I aim to develop more hypertext and analysis of how this book endures throughout 2024.