Some thoughts on James Gleick’s The Information.

“The alphabet is like a contagion – both the virus and the vector of transmission in and of itself.”

Back in the “learn to code” days – a phrase shot off in mean spirit by anti-intellectuals to journalists and academics who were loosing their jobs by the thousands – I dipped my toe back into the world of coding. I hadn’t touched the back end of things much since my high school days when I took a web development elective which had the sole purpose of updating the school’s website through Dreamweaver. A semester of HTML. Fun? Sure, but an annoying nightmare of repetition (we never got around to CSS).

“Learn to code” brought me to the Khan academy and the preliminary ideas behind Ruby and Python. These were languages like any other, why shouldn’t I pick them up and learn how to use them? I suppose in the same way I never quite picked up the linguistics of mathematics – because they were never taught as languages are taught – first through immersion and survival, then through refinement and structure. Just as a child learns language by listening to and engaging with their parents and peers – we know how to speak it long before we know how to read it. Every language we attempt after is the inverse – learn the reading and writing, then we’ll get around to pronounciation.

James Gleick’s tome on information is nothing short of fascinating. Then again, this is the kind of stuff that fascinates me. For years I have been thinking on the problem of a forever-connective internet – a place with no broken links or 404 errors, a place where referred material still exists, and nothing is subject to a destroyed server or corrupted hard drive – of which I have quite a few. However, The Information was published in 2011 – very much in the “online era” even though the internet is still in its teenage years. Social media wasn’t yet the monster it would become and the biggest issue he ponders on is what should go into Wikipedia.

Everything before that is assured and reliable as history has a way of not necessarily creating anything new (although, new things are unearthed, and perspectives shift around – but the events largely go unchanged).

“He that desires to print a book should much more desire to be a book.”

-John Donne

The big ideas I took from this tome:

Every information medium has an “Event Horizon.” A place where it dies off and is replaced by something more capable for the current era, even if it has to stutter a little to get there. Such as live performances to recordings, to radio, 8-track tapes and cassettes, to CDs. After the publishing, I’m sure he would have dived in on the implications of streaming and DRM management – what information gets the right to exist or be monetized. I’m sure Gleick would have loved looking into the idea of the resurgence of vinyl and physical media.

As I like to tell the digitally obsessed: the most punk rock thing you can do is buy used books. (or, go to the library, depending on who I’m talking to. But you should also go to the library).

The idea of the alphabet was first established in the area now known as Palestine. 33 characters established as a way to standardize the various languages of the region. We were knowing the idea of “a world beyond.” And perhaps this was the attempt to rebuild Babel? Alphabets may be standard from one language to the next, but the mix of those characters is still very much a cultural pull.

Written language allows for abstraction. Speech is far too fleeting to build upon – the same way a group of friends can get wild over an idea while knocking back a few beers, only to have the same idea fall flat the next day. Yes, historically traditions and ideas were passed down in an oral tradition – something that we can’t comprehend today – we are far too removed to understand how an oral-only society might exist.

“Language is not a technology – it is what the mind does.” One doesn’t exist without the other, at least not by today’s terms. So, what was our mind before language? Yet, language, written language, is just external characters which are no part to themselves- they are signs for other signs. Also worth noting: Oral languages top out at around 8,000 words. Meanwhile, the English language has millions of words and is growing by the thousands each year.

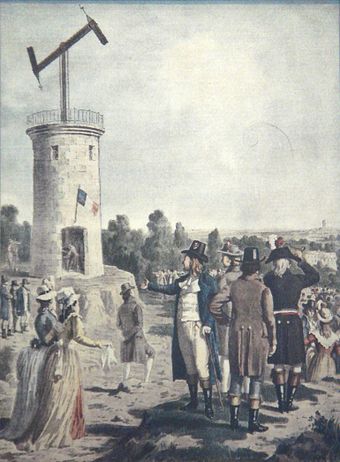

The speed of language. The invention of the telegraph after years of trying (and ultimately failing) to get a semaphore system in place. Semaphore networks could max out at three signals a minute (far less in bad weather). A sentence could take over an hour to transmit. With the spread of trains came telegraph, and not long after the observation: “Intelligence hastily gathered and transmitted has its drawbacks, as it is not as trustworthy as news that starts late and moves slow.

In 1837, the telegraph was banned in France. Probably for the best. Kidding! Consider the wars, the loss of centralized power, the spread of misinformation. Of course, it would make sense for the powers that be outlaw such things.

The Library as the Universe – something that is created and ever-changing. We don’t’ necessarily “own” our information anymore, most of whatever can be found at a moment’s notice with search and filters. “At any moment the reader is catching a version of truth on the way.”

This brings about the anxiety of the infinite playlist – fulfillment is replaced by anxiety, the addictive cycle of craving and malaise. As soon as you have started the experience of a song or book or movie, you’re immediately thinking of what else is out there. (paraphrased from Alex Ross). The quandary of too many mouths, not enough ears. We’re making more information than could ever be consumed in a thousand lifetimes – why?

We end up relying on critics and tastemakers. We look to others to tell us what to consume, listen to and think. Why? Because “of the short supply and limited capacity of minds.”

We are now all patrons to the library of Babel.

“We shed as we pick up, lost text will turn up again in another time, place, language.”

– Tom Stoppard, Arcadia.